It is not generally a good sign when the blog is silent for so long. It tends to mean that either nothing at all is going on in my life, or there is far far too much going on in my life. This has been a far-too-much time. And it’s funny, isn’t it, the way life works. After 10 days of full-on work, with me go go going all of my waking hours, I have come to find myself sitting on the floor of the Rotorua airport, plane cancelled, people trying to figure out what to do with us next (the last plane tonight is already full in this tiny airport), and nothing at all to do. Isn’t life funny that way?

I have been planning and then teaching a couple of leadership development programmes and then writing and delivering a speech. Each of these pieces is another root in the soil here, another beginning at building something here. And each is an open door with no clear sense of what might happen next. In the whole world, I think, we don’t know what’s going to happen next. The thing that strikes me is that not knowing what’s going to happen next isn’t catching me anymore. Do we move back to the US? When? Who knows. Will we ever sell the Ocean Road house? Who knows. Will I get another contract for this leadership development work or any future contacts from this speech today? Who knows. It’s all feeling so impossible to understand that I can hardly even bother trying anymore. Instead I’ll bump bump into the clouds and hope to come down safely on the other side.

One of the things that happened in this busy time was that it was the first time one of my kids was hurt by another kid at school. It was in many ways, exactly the way you think it would be with Aidan. From multiple accounts, it was a whole system effect. Naomi was teased at lunch and tattled on the teaser. The teaser didn’t like it and became agitated with Naomi. Aidan came over to check on the agitation. The teaser’s big brother (and this fellow is seriously big, a head taller than Naomi even) got involved and told Naomi of his displeasure at the fact that she had tattled. Aidan piped up that he didn’t want his sister talked to that way. And then the big boy, who has a long-standing problem with violence, knocked Aidan to the ground and kicked him twice in the back, hard. I got a call from the principal at the close of the first of my many events last week, and madly checked in with all players. Aidan was sore. Naomi was shaken. Rob and Michael were angry. And I ached with all the pain of it all.

We talked and talked about the incident and about what was going on there. Aidan was anxious about this boy seeing him again when he came back to school after the suspension. Naomi was anxious about whether Aidan might be seriously hurt from the kicking and pleaded for us to take him to the doctor. She was feeling at least a little responsible because it was her tattling that made the boy angry at her in the first place. We tried to take the various pieces in turn. Off Aidan went to the doctor, to have a variety of precautionary and non-invasive tests to see whether his kidneys had suffered from the blows (they hadn’t). Naomi, suddenly realising that she was not the centre of attention, began complaining and carrying on. All of us were shaken, all needing to connect with one another and hold on to the fact that while something really bad could have happened, nothing really bad actually did happen.

Naomi and Aidan were amazingly gentle with one another for the next few days. I would walk into the living room and find them sitting tightly next to each other, reading silently. We turned toward talking about how Aidan was feeling about the boy, about whether he was afraid of him or angry at him., and what he would do when the boy apologised. “I already know what I’m going to say, Mom,” he told me. What? “I forgive you?”

I keep thinking that I have already reached the height of the love I can feel for these people, but it turns out that there are moments—filled with joy or filled with fear or filled with angst—that increase my love. And as these children grow, I find that my love and admiration for them grow as well. And it turns out that even in this busy time, everything is growing in Paekakairki.

This blog has turned into a tale of two different journeys: one we picked and one that picked us. In 2006, we moved to New Zealand to create a new life. In 2014, Jennifer was thrown into the world of a breast cancer patient. Here she muses about life and love and change. (For Jennifer's professional blog, see cultivatingleadership.com)

28 February 2009

12 February 2009

attachment

Having a pre-teenager in the house is a constant addition to my practice of non-attachment. There is so much I want to hold on to, so much I have to let go of. Just this morning, for example, when we needed her to find an overdue library DVD, Naomi put on her long suffering voice. “I am trying to eat my breakfast and get ready for school, which is the most important thing in the morning,” she told us, in an exasperated tone I recognise as mine. “You will just have to wait for a more appropriate time to be searching for things.”

I can actually feel my buttons being pressed. And the thing is, there are buttons all over the place on this one. There’s the don’t-you-use-that-tone-of-voice-with-your-mother button, there’s the don’t-shirk-your-responsibility button, there’s the oh-crap-am-I-so-obnoxious-when-I-say-those-words button. Some of them are about me, some are about her, some are about us.

I find that I am attached to SO many things right now. I am attached to her manners, to her thoughtfulness, to her helping around the house. I am wanting her to care less about brand name shoes and be more tolerant of my love for buying used clothes. I’m wanting her to be less focused on her stupid teen magazines and be more aware of the ways the world needs our assistance (and not another Disney band). I want her to be less demanding and more grateful for all the wonderful things in her world. I am attached to being the kind of mother who supports her kid and also the kind of mother who guides her kids toward something finer than they might be if left to their own devices. It turns out that when I come to Naomi, I am attached to everything.

And this is not the time for attachment, this is the time for separation. This is the time for letting this smart, beautiful young woman begin to find her way in the world. This is the time for showing up as the mother of a nearly-teenager, not as the mother of an almost-kid. The time for understanding that “Mom, I don’t want you to sing in front of any of my friends ever again,” is a way for her to control and name her own world, and not just a slam on me or a glossing over of the 11 years we’ve spent singing together.

I was shallow and brand-conscious when I was 11. I collected stupid girl magazines and talked too much on the phone with my friends. I wanted things my own way and cried when I didn’t get them. I was Naomi in my own way. I’ve turned out ok.

Now I have to be me in a new way (again and again in this parenting journey). I have to take her mood swings as the pattern of my life, a pattern I teach about in classes about development all over the world. I have to remember what I tell clients all the time—that I am not so much wanting particular behaviours from Naomi but particular thoughts and feelings about the world, and that wanting someone else to feel a particular way is a losing battle. It’s ok to demand that she set the table each night; it’s not ok for me to insist that she must want to set the table in order to contribute her share to the house. It’s ok for me to demand that she be respectful; it’s not ok for me to insist that she must feel respect for me all the time.

Last night I was cleaning up from dinner and she wanted to sit in my lap, and then, later she wanted to cuddle for a long time. In most circumstances, I’d have put her off until later—cuddling after work is done. Things are changing, though, and just because I’ll want to hold her later as much as I want to now does not mean she’ll be in that same space. So I stopped what I was doing and stood and held this little big girl, this child-woman nearly as tall as me, for as long as she wanted to hug. I tried to memorise the scent of her hair and her thin, growing body in my arms, remembering the scent of baby shampoo and slightly spoiled milk that was baby Naomi, the pudgy infant I thought I loved so hard that my heart would break. Soon she will be in a different phase and I’ll be holding a different version of Naomi, and my heart, older now, will still threaten to break with the surfeit of love.

This morning, mad at me because I would not walk home through the rain to pick up a permission slip she had left behind, she stormed off the last little way to school without a backward look. Everything in me screamed to go after her and tell her she couldn’t treat me like that. I have learnt that, at least in a momentary way, I can be as made of anger and indignation as I am of love.

I am attached to her being the same and I am attached to her growing. I am attached to her being her own person and to her being exactly as I want her to be. My attachments pull on me and cause me trouble, and in every instance my own ambivalence is mirrored and distorted by the many ways she is holding on to all the same complexities of growing up. And so I hold her when she wants to be held, and I let her storm off when she wants to be angry, and I try always to hold myself as she grows. When she was a toddler, beginning to show her strong-will and fiery personality, I used to stand over her crib at the end of a long hard day. “I love you for everything you are,” I’d whisper to her—and to me. “I love you for the good things and for the hard things and for every cell in your being because that is what makes you Naomi and that is just who I want you to be.” I tried then to remember that valuing a person for the fullness of who she was—for her faults as well as her gifts, for her weaknesses as well as her strengths—was the true measure of love. I want to hold on to that way of loving her, and the rest—my particular desires and hopes and impulses—is all just noise. Everything else is just my construction of shoulds. Now is the time to let go of my constructions and open my eyes to the person she is becoming. Perhaps that is a goal I could be attached to.

04 February 2009

cycles

As I begin this blog is it is a grey morning here at the beach, clouds gathering over the hills which have faded this summer from emerald green to olive to a tawny brown. Yesterday was the first day of school. The kids are in new classes with old friends now, the pattern of life in a tiny village school. This is a new year, a new cycle, and new and unexpected things are going to happen. There are ways that our life here feels more familiar than it ever has before. We walk into a house we know well, we come home to sugar-sweet grape tomatoes dotting the garden, we putter with Rob in the kitchen and drink tea with Melissa in the lounge.

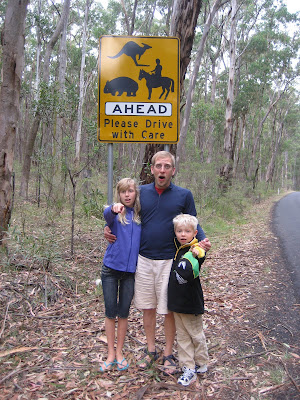

And while things are familiar, it is a strange new world. We have come home from Sydney, a magnificent city which is half American in its self-conscious display of wealth and power, its traffic and endless suburbs, and half tropical paradise with its teal water and golden sand beaches, its parrots in the eucalypts (pictures today are from the Botanic Gardens at sunset at the end of our trip—those cockatoos are wild and fly in flocks through the garden, shrieking indignantly). We are back to home, where the rhythms of life mean that the days begin to get shorter here in February and the new calendar year brings a new school year in its wake. The sound of sirens and truck brakes of Sydney (and our life in the US) is replace by the changing but constant roll of the sea. Where were we again?

Now, though, as I come to terms with my own private adjustments, as I live out my own private changes, the world rumbles and blows around. A

s I recover from writing my letter of resignation to GMU last night, I have friends who are reeling from job layoffs, from rapidly changing financial circumstances. As I look at my kids, so big as they walk to school on their first day of school, I have friends who are beginning their first days of work in the Obama administration or are searching for the next big thing they’ll do now that the PhD is finished. As I worry about paying the mortgage for not one but two houses in New Zealand (?!), I hear news reports predicting a dire future—total environmental and economic meltdown. Obama offers a new kind of hope—I have had the new experience of having my president quoted as an example of a GOOD leader again and again this week; the financial and climate news is dire.

s I recover from writing my letter of resignation to GMU last night, I have friends who are reeling from job layoffs, from rapidly changing financial circumstances. As I look at my kids, so big as they walk to school on their first day of school, I have friends who are beginning their first days of work in the Obama administration or are searching for the next big thing they’ll do now that the PhD is finished. As I worry about paying the mortgage for not one but two houses in New Zealand (?!), I hear news reports predicting a dire future—total environmental and economic meltdown. Obama offers a new kind of hope—I have had the new experience of having my president quoted as an example of a GOOD leader again and again this week; the financial and climate news is dire.There are some rhythms to life that are predictable and known. The school year comes and goes. In the pattern of growing girls in the modern era, Naomi gets taller and more willowy; spends more time in her room, door closed, listening to music; tosses her head and goes to school without a backwards glance at her waiting mom. The dog begins to go grey in his muzzle. The mom, watching growing children, holds babies with a new kind of melancholy, frowns at the coming wrinkles (thus making them worse), wonders whether it’s really a good idea to hang the new full-length mirror in the closet. The tide changes, the moon waxes and wanes, the days lengthen and then shorten and then lengthen again.

Now, in a world of acknowledged uncertainty (because really the world was always un

certain, wasn’t it?), we can hold on to those familiar patterns as questions swirl around us. When does this global slowdown crash on these shores? What will happen in Michael’s job when his secondment is over? How do we decide how to allocate time in an era when future earnings are in question?

certain, wasn’t it?), we can hold on to those familiar patterns as questions swirl around us. When does this global slowdown crash on these shores? What will happen in Michael’s job when his secondment is over? How do we decide how to allocate time in an era when future earnings are in question?I keep wondering whether all this uncertainty is just that we’ve lost our way, lost our confidence in ourselves to be uncertain and also patterned, to predict some things about the future and not others. I wonder whether our lack of comfort with ambiguity is the real crisis here, and not the particulars of any one life story. We were once more certain than we should have been—that created unsustainable growth that damaged our economic systems and our planet. We are now less certain than perhaps we should be—and this is creating a fin

ancial gridlock and psychological peril, damaging our ability to live and to thrive. Perhaps what we need is to understand ourselves in the rhythms of the tides and the stock markets, to hold on to the ways the future has always been inside our control, and has always been outside of it. Today I will work, I will pick up the children from school and hear about new teachers and old fights, I will make dinner with lettuces fresh from the garden. The world will turn, the waves will come, and inside the regular patterns of our lives will be heaps of variation, inside the variation of our lives will be heaps of patterns. I wish for us all some peace in the tumult.

ancial gridlock and psychological peril, damaging our ability to live and to thrive. Perhaps what we need is to understand ourselves in the rhythms of the tides and the stock markets, to hold on to the ways the future has always been inside our control, and has always been outside of it. Today I will work, I will pick up the children from school and hear about new teachers and old fights, I will make dinner with lettuces fresh from the garden. The world will turn, the waves will come, and inside the regular patterns of our lives will be heaps of variation, inside the variation of our lives will be heaps of patterns. I wish for us all some peace in the tumult.

01 February 2009

more pictures, now that we're home

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)